“THE MAGNIFICENT scarlet robes that adorn the judges of Germany’s constitutional court trace their origins to a spot of judicial attention-seeking. Soon after the court was established in 1951, its judges decided they needed to distinguish themselves from their peers on the Federal Court of Justice, and recruited a theatrical costumier to update their look. Yet, as the judges showed on May 5th, their rulings can be even more eye-catching than their attire.”

That’s how The Economist started its article on the mind-boggling presentation of the German Constitutional Court (GCC) on May 5, 2020.

It is conceivable that Andy Vosskuhle and his entourage of judges would have preferred that “group of hard right politicians and economists (and for these purposes, they can be presumed to be the same)” would be rather six feet under had they placed, yet again after 2014, an action and the court had to deal with it. Back in 2014 the GCC got rid of it by simply transferring it to the ECJ and FT Alphaville asked “The OMT — um, what does this thing do again? A Bundesverfassungsgericht guide“.

May 2020 proved to be different. By a lot. Perhaps Andy Vosskuhle thought it’s my last day on the job anyway, so I might as well go with a bang and kick some ECJ ass. That he did. Kicking ass is fine, as long as you are right. Yet with his statement “The Court of Justice of the European Union exceeds its judicial mandate” his court was completely wrong. It did not take long and the ECJ punched back.

In a sharp rebuke of the German Constitutional Court (BVerfG), the European Court of Justice (ECJ) asserted that it alone had jurisdiction over the European Central Bank (ECB).

“In order to ensure that EU law is applied uniformly, the Court of Justice (ECJ) alone … has jurisdiction to rule that an act of an EU institution is contrary to EU law,” a statement said.

“Divergences between courts of the member states as to the validity of such acts would indeed be liable to place in jeopardy the unity of the EU legal order and to detract from legal certainty.

“Like other authorities of the member states, national courts are required to ensure that EU law takes full effect. That is the only way of ensuring the equality of member states in the Union they created.”

As the FT reported

A bombshell ruling by Germany’s constitutional court questioning the legality of European monetary policy impinges on central bank independence and imperils the EU legal system, former policymakers and legal experts have warned.

The court on Tuesday ordered the German government to ensure the European Central Bank carried out a “proportionality assessment” of its vast purchases of government bonds to ensure their “economic and fiscal policy effects” did not outweigh other policy objectives. It threatened to prevent the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, from making further asset purchases if the ECB failed to comply within three months.

Berlin MMT economist D. Ehnts comments thus:

In today’s ruling, the Federal Constitutional Court upheld several constitutional complaints against the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), stating that the ECB’s decisions on the Public Sector Purchase Programme were incompetent, as the proportionality had not been assessed:

A public sector purchase programme such as the PSPP, which has significant economic policy implications, requires in particular that the monetary policy objective and the economic policy implications are identified, weighted and balanced against each other. Therefore, the unconditional pursuit of the monetary policy objective of the PSPP to achieve an inflation rate below but close to 2 %, while ignoring the economic policy implications of the programme, appears to disregard the principle of proportionality.

The necessary balancing of the monetary policy objective with the economic policy implications of the means used does not follow from the decisions which are the subject of this procedure. They therefore infringe the second sentence of Article 5 (1) and (4) TEU and are not covered by the ECB’s competence in the field of monetary policy.

In my opinion, this assessment is adventurous. A central bank has a big hammer – interest rates – and almost as big – the rules on what collateral is accepted for central bank loans. To be able to influence interest rates in the long term, a central bank buys and sells government bonds. In the euro area, this is done through resale transactions (so-called repos = repurchase agreements). This is fundamental – without trading in government bonds, the central bank cannot influence interest rates and yields. (Technically, it would be possible to set interest rates in such a way that the interbank market rate is set without the central bank buying and selling government bonds, but this requires that, in case of doubt, government bonds can be bought in large quantities by the central bank. This is not permanently fulfilled in the euro zone).

Before he points out some hair-raising assertions of the GCC:

For example, there are significant risks of loss for savings. Companies which are no longer economically viable per se remain in the market because of the general interest rate level, which has also been reduced by PSPP. Finally, as the duration of the programme and the overall volume increase, the Eurosystem is becoming increasingly dependent on the policies of the member states, as it is becoming increasingly difficult to terminate and unwind the PSPP without jeopardising the stability of the monetary union.

Could the SNB please explain to the Central Bank at what exact interest rate ‘non-viable companies’ have disappeared? That is outrageous. Such an “equilibrium interest rate” may be haunting the minds of some errant economists, but that is not something that can be seriously advocated! What comes next? A lawsuit against government spending because it keeps “businesses that are no longer viable” alive? This approach presupposes that there is a balance in the economy and that it can be observed. I do not consider both of these conditions to be fulfilled. This argument should therefore be rejected.

Scott Sumner points to a rather funny tweet.

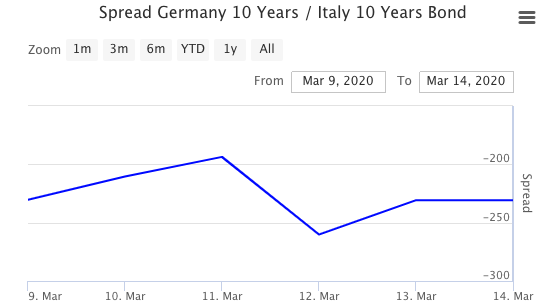

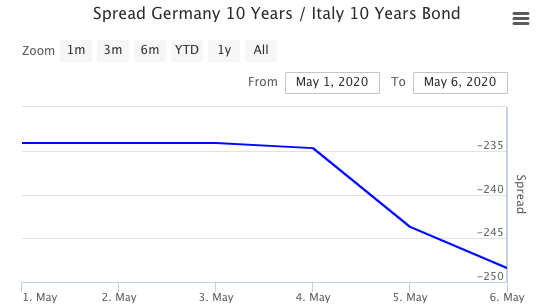

The General Theorist compares the bold GCC decision to a “fishing exhibition to find some technicality to trip up the ECB’s public sector purchase program (PSPP)”. Lamenting the “principle of proportionality” is like finding a hair in the soup. While the GCC admits that “it is not ascertainable that the purchases under the PSPP manifestly circumvent the prohibition of monetary financing” but “in light of the volume of bond purchases under the PSPP, which amounts to more than EUR 2 trillion, such a risk-sharing regime, at least if it were subject to (retroactive) changes, would affect the limits set by the overall budgetary responsibility of the German Bundestag”. IOW, don’t even think about making the German people responsible for the risk carried in the handling of peripheral government bonds! Perhaps nobody has explained to those illustrious judges what a spread of, say, -240 bps between the It/G bonds means: who pays and is is being paid when borrowing?

Bill Mitchell, as usual, puts it plain and simple: “BVerfG decision once again exposes the sham of the Euro system“.

But it won’t surprise you to know that I think the Court made the correct judgement by exposing the complete sham that the European Union and the Eurozone, in particular, has become – an illegal, look-the-other-way, neoliberal cabal that the Union has become.

I do not fully agree with this assessment as the court’s intention is to keep German taxpayers of the hook while reaping all the benefits (in the sense as the GCC understands the whole concept of the ECB’s QE program). It is rather as DEALBREAKER puts it:

It’s no secret that the Germans have had their differences with the European Central Bank which, while it has not been as profligate as certain members of the Eurozone and was certainly useful in bringing Greece to heel, was also perhaps a bit looser with the purse strings under a citizen of one of those members than it would have been under a properly tightfisted Teuton. This lingering frustration with the spending of German euros on things Germans do not want is certainly felt by the members of Germany’s Constitutional Court, which chose this week to express those feelings by essentially declaring the ECB unconstitutional under Germany’s Basic Law.

Here is CNBC:

“The court is asking the central bank to show that it took into its decision the proportionality principal,” Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, chairman of Societe Generale and a former member of the ECB’s executive board, told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” Friday.

“Frankly, to think that the ECB did not do that is laughable — there is plenty of research, of reports, of statements, that clearly show the ECB doesn’t just meet in five seconds and say ‘let’s just raise rates or cut rates’ out of the blue. There is a very deep analysis, discussions, arguments, and sometimes disagreements.”

A former president of the German Buba sees the “Future of Europe is at stake” and rightly points out:

The Karlsruhe court judged that the ECB exceeded its powers as a result of inadequate consideration of the legal principle of ‘proportionality’. However, the court is skating on thin ice when it demands, as criteria for ‘proportionality’ of a government bond purchase programme, the ‘identification, weighing and balancing’ of the ‘monetary objective’ and ‘economic impact’. The court mentions savers, shareholders, property owners and insurance policy holders, among others. But the list fails to include taxpayers and employees, who have mightily benefited from the ECB’s policies – a truly astounding omission.

One can ask whether savers with money in German savings banks have not fared rather well, at least in the recent market downturn, relative to other groups such as shareholders. The German government’s revenue surpluses surely outweigh interest foregone in savings accounts. Some economically unviable companies have, as the court says, remained afloat, but many have used low interest rates to invest, create jobs, and service their bank loans – a positive contribution to the economy and to society.

Another contributor on OMFIF detects a “Revenge of the German constitutional court” and points to a speech by none other than the German member of the ECB Isabel Schnabel which the GCC apparently did not read. He cautions “Ultra vires. Ultima ratio. Beware of Germans using Latin.”

Yet another chap on OMFIF is more conciliatory and sees a “Key role for Bundesbank after German court ruling” He sees the ball in the court of the ECB.

The ball is now in the ECB’s court. The central bank does not lack legal expertise, starting from its president, Christine Lagarde, a lawyer by training.

Seriously? Well, here is the ECB. BANG!

Christine Lagarde has fended off criticism of the European Central Bank’s government bond purchases, saying she was “undeterred” by an order from Germany’s highest court to produce a justification of its action.

This commenter has a suggestion how to respond to the Karlsruhe Klowns:

I think that the ECB should troll the German court and answer truthfully:

“Sorry, we are not acting proportionately at the moment, we should do so much more. We should at least convey in a credible way that we will do whatever it takes.”

It should also be kept in mind “… as a reminder, the last German declarations of war did not go well“.

Lastly, here is Wynne Godley in “Maastricht and All That”:

What happens if a whole country – a potential ‘region’ in a fully integrated community – suffers a structural setback? So long as it is a sovereign state, it can devalue its currency. It can then trade successfully at full employment provided its people accept the necessary cut in their real incomes. With an economic and monetary union, this recourse is obviously barred, and its prospect is grave indeed unless federal budgeting arrangements are made which fulfil a redistributive role.

There is a good chance the GCC will have to meet again over PEPP. What a mess. What a system this Eurozone.